Published 2004 on BrandChannel.com

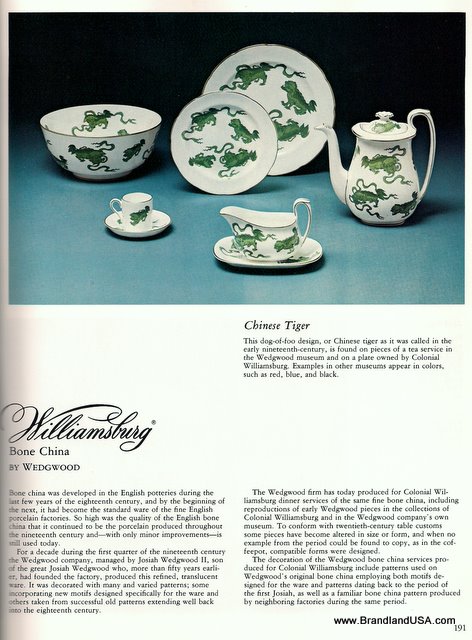

Just 20 years ago, if you wanted a piece of Colonial Williamsburg, you could go to New York’s Fifth Avenue, where the restored Virginia town had a shop in the genteel department store B. Altman. There, you could select Wedgwood bone China patterns, order a mahogany Chippendale-style highboy chest (custom made by the Kittinger Company of Buffalo, New York), or buy a Queen Anne-style gold leaf and gesso looking-glass. Confused about gesso, Chippendale or Queen Anne? The 300-page Williamsburg Reproductions catalog, a sort of WASP pornography, not only described each item in excruciating detail, but offered up pages upon pages of design ideas as well as a glossary of furniture words like ogge, splat and burl, and a chart of Williamsburg-brand Martin Senour paints.

Today, B. Altman is closed and Kittinger, which went through a round robin of corporate buyouts, is no longer with Williamsburg. For decades, Williamsburg’s licensee was Josiah Wedgwood, the old-line British company that is now Wedgwood Waterford. Today, Wedgwood partners with super-luxury brands like Bulgari and British designers like Basia Zarzycka and Jasper Conran. On the other hand, Williamsburg now sells colonial reproduction plates from China maker Lenox, which partners with Zales, that mall jewelry store. Furniture is not always copied in “excruciating detail,” but instead can come Crate & Barrel-style, made by the Massachusetts company Nichols & Stone. Certainly nice, but a touch more mid-market than before.

The catalog has changed too, everything from tchotchke colonial figurines to pineapple “Welcome” signs that, dare we say it, hint at Lillian Vernon. Table lamps are sold at Lowe’s, the big box hardware store. Online (and on sale for US$ 7.50 at williamsburgmarketplace.com) are “orange cream” smelly candles reminiscent of something in a suburban Kirkland’s, or a Cape Cod tourist shop. Williamsburg, once known for design leadership, has begun to ape its imitators. At its core, Colonial Williamsburg is a town that became a brand and it is that brand that is in jeopardy of descending into a “ye olde” parody. Like Gucci, it needs a reinvigorating Tom Ford who can navigate a tenable path between hip, history and brand expectations.

It’s a different era for Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, born of success in convincing millions that they could get that Colonial America feeling through Williamsburg. That success spawned imitators. House museums like Monticello and Winterthur have ratcheted up their licensing, and now are destinations-cum-catalogs. In addition, Williamsburg’s retail look has been copied by everyone from Ethan Allen to Bombay Company. While Williamsburg is trademarked, the town is not, which allows local retailers like Williamsburg Jeep to borrow the mystique.

Today, the Foundation is fighting for its life. Last year, visitation was down to under 800,000 (dropping since 1995) and the Foundation lost a stunning US$ 35 million, according to the Associated Press. Those who observe the situation think there is still a market, but it is by no means assured; even beloved Cypress Gardens closed. “I don’t think cultural tourism is dying,” says Ken McCleary, a Virginia Tech professor of tourism and hospitality. Instead, McCleary says that the new attractions like Vegas hold more excitement. “There is so much more competition for that kind of stuff.”

Williamsburg must get a lot right, all the time, as the scope of what its thousands of employees do is beyond most any other brand. It is first a US history museum (actually a couple of museums and dozens of exhibition houses), both indoor and outdoor. It is a landlord, renting houses to employees and guests (a recent exec was, upon hiring, delighted to be handed a skeleton key when he took possession). Like a theme park, it runs parades, bands and dress shops. Like an historical society, it runs a public archive. Like National Geographic, it has publications, a documentary unit and archaeologists. Like any company town, it runs restaurants, hotels and bus routes. Williamsburg has national experts in textiles, furniture, decorative arts, costumes, even fake-food. It also makes products; last year, it began selling silverware, leather bound books and cedar buckets made in the shops.

Williamsburg is one of the world’s great experiments in brand revival. In the 1920s when John D. Rockefeller Jr. first became interested in the former capital of Virginia, it was to restore or rebuild the main public buildings because of associations with past US presidents Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. Taverns in town were fully reborn and rebuilt as real restaurants — Christiana Campbell’s, Shields Tavern, King’s Arms and Chowning’s. Today, each is a separate concept with its own menu, logo and product licensing.

As the tourists came, other brands began. First there was the luxury Williamsburg Inn, which Rockefeller envisioned as the sort of place Rockefellers would stay. Then came the Golden Horseshoe Golf Club and the Motor House (yes a motel!). Part of the brand appeal was the magic Rockefeller touch. After all, John D. Rockefeller Jr. simultaneously created Rockefeller Center and Colonial Williamsburg.

Through the years, Williamsburg led taste and trends. Synonymous with quality and good taste, Williamsburg had snob appeal without alienating the average tourist. In 1983 it even hosted Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher at the G-5 Economic Summit. Today, the mix appears not to be working.

Hoping to capture a “silver lining” from September 11, last summer CW defensively issued a poll stating that half of the US was not taking a summer vacation. It closed its nearby plantation Carter’s Grove, and is selling off real estate. It will close and move the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum. The venerable Craft House, CW’s cozy department store, will be torn down, and the retailer moved. Tourists now go to the Craft House to photograph it before its destruction later this year, certainly a curious position for a preservation non-profit.If there is one criticism that folks at Colonial Williamsburg hate, it is that Williamsburg is Disney – a 300-acre colonial theme park of fife corps. But the parallel with Disney (or EPCOT) is eerie. It was no secret that Uncle Walt was fascinated with Williamsburg; the restoration of Duke of Gloucester Street predates Disneyland’s Main Street by 25 years. Its resort Williamsburg Inn also predates Disneyland’s resorts. Like Disney, CW is at a crossroads. Does it take the Roy Disney route, and go back to its roots? Does it follow Michael Eisner, and stick to its guns? Or does it reinvent itself with a new partner like Comcast?

Certainly, the problems are a result of changing fashion. Williamsburg has always prided itself on historical accuracy and that comes at a price. Today, the CW newspaper uses a shirtless, sweaty black slave with flames coming out his head and a sharpened hoe as if ready for race war in its marketing communications. Whether that is a complete picture of colonial history is debatable; that it does not appeal to its core white, upper middle class audience is undeniable. In the old days, Williamsburg hired costumed guides who discussed the furniture and architecture; today there are “interpreters” who play characters. While many like it, it is expensive and alienates high-end guests who would rather have scholarly descriptions of ogees and gesso.

Much is right, however. Williamsburg hired Quinlan Terry, the British architect and favorite of Prince Charles, to add onto the retail downtown Merchant’s Square, a retail area which bucked the downward trend of just about every American downtown. It restored the pre-Hawaii Five-0 Jack Lord movie, The Story of a Patriot. It even continued the annual Antiques Forum, which attracts collectors to the Williamsburg Lodge. Wisely, it has reserved the “4 XX” reproductions logo for copies from the collection. And it’s still clever — one of the more amusing mascots sold is Wellington, the Leicester Longwool Sheep, a stuffed reproduction of a Williamsburg rare-breed sheep.

Furthermore, Williamsburg still can provide a bold marketing flourish; on President’s Day in February, it placed an intellectual ad on The New York Times’ op-ed page to celebrate Lincoln and Washington. It includes its bold new marketing slogan, “America. Chapter I.” which is certain to appeal to the core audience of upper middle class families. Let’s hope it works. While Williamsburg might be America’s first chapter, it would be a shame to write Williamsburg’s last.

John Garland Pollard is a Virginia magazine editor. While in college in the ’80s, he worked at the Craft House and counts as one of his great childhood achievements winning a pie-eating contest in a public “faire” in the Governor’s Palace Garden. This appeared March 1, 2004 on Brandchannel.com